©January 2001

Carol Jane Remsburg

Daddy and the Lights

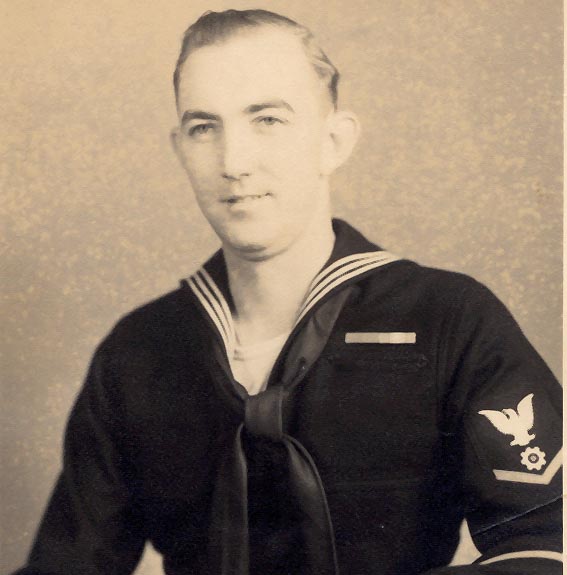

Daddy

was born June 19th, 1929—just before the advent of the Great

Depression. If there ever was a man

born to frugality, it was him. Don't

get me wrong, Daddy wasn't above splurging on his kids or his family and

friends, but it was rare he ever did for himself. And when it came to certain things concerning day-to-day life in

our family then his vision could be very narrow indeed.

When

I was three, the family settled into the house I would grow up in. To me it was a great house with plenty of

room—although it had certain drawbacks.

It was Daddy who figured out the ways in which this house could work

without too many major changes—thus saving money by not expending it. The house was one of many built just after

WWII. It was sizeable enough but had

flaws that when the '60s and '70s arrived grew glaringly apparent. Everything ate electricity!

The

boondoggle of a house only had a 60-amp service to it. Therefore running the dishwasher and the

dryer or the air conditioner in the den at the same time was sure to blow a

fuse. Only one could run—no exceptions

could be made because the system in the house was unforgiving. Push it and it blew. There wasn't a soul in the house that didn't

know to shut one off before starting the other—no matter how old you were. When we blew a fuse, we also knew how to

reset it and quickly before someone found out what we'd done.

With

the dryer on the same circuit as the water heater, the same could be said. Yet if the dryer wasn't running and that big

plug wasn't changed then the clothes were taken out—somebody got a mighty cold

shower. Guess who it usually was?

The

damp cellar had wire hung for hanging clothes during the winter months and we

tended not to use the dryer at all if we could get away with it. That was until my sisters got into their

teens and then everything had to be dried in the dryer and line dried clothes,

either inside or out, became not only passé but damaging to the reputation. We only had so many clothes and their stylish

ones were minimal and worn with regularity.

Daddy

was of the soft-spoken sort. He was

sweet and gentlemanly. He was

knowledgeable and kind and loving.

However living with four other females and only one bathroom in the

house, things weren't ever easy for him.

When he did manage a bit of privacy in the privy to find the water in

the shower frigid—singing from the shower wasn't what we heard. It sounded more like a bull moose with blood

in his eye to me. If you were at all

ambulatory, you fled the house by the fastest means possible. We were lucky; his ire wasn't the kind that

lasted for very long.

As

we all adored him, we all tried very hard to keep those experiences

limited. Usually though, he would be

last in line in the morning for a shower and got the short-end of the hot water

anyway. It was a good thing he tended

toward those military style showers. As

teens, we girls would shower until the warmth was gone. He hated that and nagged us to no end about

it.

However,

if there was a bugaboo in Daddy's soul, it was over the lights in the

house. If you left a room, all

electrical appliances and lights should be out. It drove him nuts over the fact that we could exit our bedrooms

with lights and radios alive while sauntering into the living room or the den

to plop down and watch some TV.

Daddy

would and could let us slide on many things, but on this issue he gave no

quarter. His frown would be

intense. I couldn't stand it. I would try and fail again and again over

the light issue just as my sisters did.

It would be years later that this same quirk would come to haunt

me. I had finally learned what he

wanted me to learn. Waste is

expensive. A watchful eye and a few

seconds of thought costs you nothing.

For

years Daddy would patrol the house over the lights and the appliances in every

room where no one was using them. Off

they went one by one and his proclamations were short and often to himself he

thought. Usually one didn't need the

lecture, just the look.

Of

course we had heard the requisite tales of "When I was growing up"

from both Mom and Dad. And although Mom

had suffered a tad harder in her youth, Daddy's tale over the frozen glass of

water on his nightstand always stuck with me.

Privation was something both my parents had known. And while they didn't wish us to suffer it,

they also wanted us to appreciate things on a basic level. Growing up, none of us reflected on it or

really cared. Their teachings came home

later on—when I had my own bills to pay.

Every

fall I close up the vents beneath the house.

I have my heating system inspected and tweaked into fine tune. I cringe whenever I have to use the dryer in

the worst of winter weather rather than having nature do it outdoors. When the air conditioning runs in the summer

I'm sure to set it at 80o while shutting all the blinds to help keep

the house cool. The same follows in

winters as I open the blinds, but I'll keep it at 72o because hubby

and daughter will freeze if I push it lower.

Then

there are the lights. Every appliance

and light that is running and not being used is ruthlessly turned off. I pace the house and check the perimeter in

intervals. My husband and daughter

don't seem to understand. The lights

cost little but it's that carry-over from childhood that's difficult to

break. Often I do this without

conscious thought. It's just something

I do.

My

daughter is hosted with things I couldn't even dream of as a child, all her

desires are met if I can manage them.

Still it's that conspicuous consumption of energy that unnerves me.

About

the only thing I will gift myself is one of hot water and that long

shower. Oh, I know it costs and I

apologize often to Daddy for it. That's

my bugaboo. If Daddy were still here,

he'd just shake his head and smile. The

world's certainly changed since his time, but not all that much. The lights still get turned off in my house.